The Play of Plays: Reality as Simulation

A journey through science, philosophy, and mind in search of meaning

I initially published this essay back in 2014. It remains one of my longest essays to date. It provides an overview of the Simulation Argument as posited by Nick Bostrom, but even if you’re familiar with the concept, I hope you can take away a new thought or implication, with the end result being an answer to the question, does it matter if reality is a simulation? Don’t just take it from me, take it from a Redditor whose comment on the original remains one of the best reviews I could ever ask for as a thinker and writer:

“Take Interstellar and Inception put them together and you get this.”

Now, eleven years and some revisions later, I bring you, The Play of Plays…

Beginning

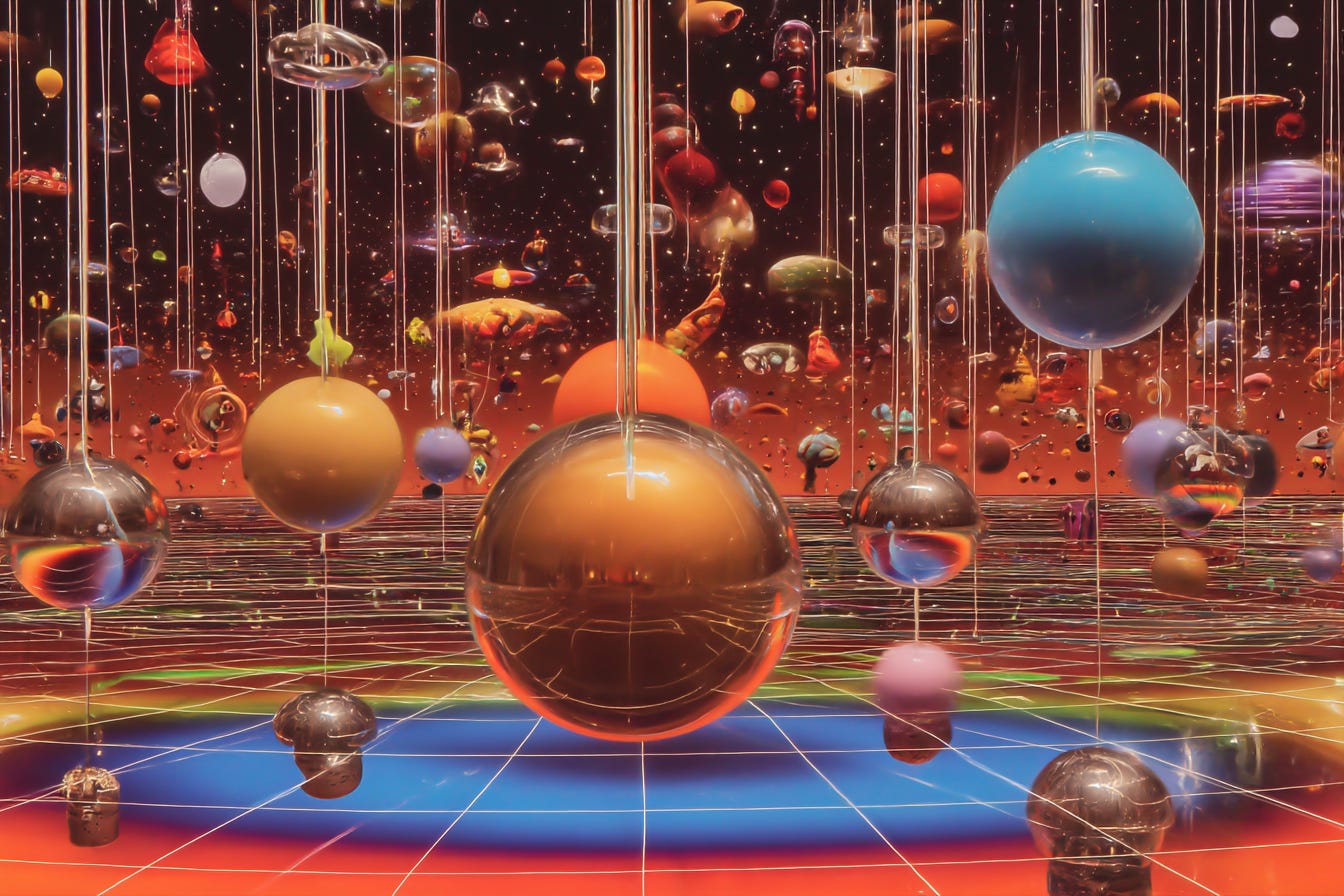

Narrative is the string that holds up the weight of humanity, instilling meaning in our lives. In the ultimate display of irony, we could be merely characters, puppets in a play written by an unknown playwright. If this is true, an ontological crisis would result from the revelation and defile our sense of purpose and meaning. When we are tempted to give up and conclude it’s The End, experience and art would push us to write our own epilogue that continues Happily Ever After.

The characters of Star Wars, Game of Thrones, and other fictional tales are undeniably alive in our minds, drawing us to tales that manifest as emotional and intellectual truths in reality, despite the fact that the stories and characters are fantasy. While literature and film remain timeless, new technologies like AI-generated content and virtual reality are changing the paradigm of storytelling, enabling unprecedented interactivity and immersion. These tools will only accelerate a narrative truth: humans have a fondness for playing God, evident in the success of video games such as Civilization and The Sims. The human experience is no longer exclusive to static stories — it is digitized in a string of ones and zeros.

Argument

Researchers and scientists currently run computer programs to understand many aspects of our complex world (see the long list on Wikipedia). As computation increases in power, we’ll be able to more accurately model representations of reality into these programs. The expected growth of computing led philosopher Nick Bostrom to pose a thought-experiment called the Simulation Argument back in 2001. Since then, it has captured the imaginations of the innumerable, questioning the metaphysics of reality in a way many find distressing. The hypothesis posits that one of the following propositions is true:

The fraction of human-level civilizations that reach a posthuman stage is very close to zero;

The fraction of posthuman civilizations that are interested in running ancestor-simulations is very close to zero;

The fraction of all people with our kind of experiences that are living in a simulation is very close to one.

The argument by Bostrom is a descendant of those devised by philosophers throughout history such as Plato's Cave and Descartes' Demon. New discoveries in science bring us closer to deciphering the truth behind these thought experiments, yet paradoxically, as we gain new knowledge, the boundary between what we know and what remains fundamentally unknowable continues to shift and transform. This is why philosophers and scientists continue to orbit the same questions, with the Simulation Argument residing at the intersection of the two disciplines. If the premise that you are living in a computer simulation seems absurd, consider any optical illusion that transfixed you with its magic, or how virtual reality can fool your senses into believing you're somewhere else entirely. With VR no longer a cyber dream, but now on the hinge of a mainstream explosion (Apple’s Vision Pro, Meta Quest), its ability to facilitate realistic immersion is the tangible proof that we can be deceived by code. The mind/brain mystery is central to the reality illusion a simulation creates — whether it’s the hard-problem of consciousness, different theories of perception, or evolution’s solutions to navigating the environment (i.e our brains don’t see what our eyes do, but construct an approximation with the data), the one thing we can be clear on is that we know far less about *what this all is* than it might seem.

Let’s investigate Bostrom’s three statements. The first, the non-existence of a post-human stage, is an undesirable state for our species. For our purposes, let’s allow “posthuman stage,” to be defined however you wish — technological transcendence, slower progress with natural harmony, etc. — we can push that aside with the assumption that this state should bring meaning and well-being to all humans in society (see my essay Between Collapse and the Cosmos for more on this). With the second statement, Bostrom explores the possibility that simulations won’t be created because humanity deems them immoral, since the beings in the simulation would experience unnecessary suffering. This ban though would not seem to be congruent with human attitudes; as Bostrom explains, we value existence. Our society holds life as a blessing, and if we could create it, the banning of it out of fear for potential harm seems unlikely. Even if simulations were banned, enforcing it would be improbable. Has there ever been an act deemed illegal that was completely eliminated from society? The other option is that simulations are not the ideal approach to fulfilling any intellectual or emotional pursuit, other advanced technologies may make simulations redundant. Given our existing interest in simulations, this possibility seems remote as well.

So, statement one seems more likely than statement two, especially if you consider the fact that humanity may go extinct before it can create advanced simulations. As I write about in the linked essay above, we exist in a precarious moment — AI, climate change, political instability, etc. — putting us at great existential risk as a species. In fact, the lack of evidence of superior alien civilizations colonizing the galaxy stirs some doubt in our survival. In another paper, Bostrom writes about the existence of a “Great Filter” that intelligent species reach, a point that puts a wall before continued existence. If we survive this delicate moment in human history, we may reach a technological Olympus, one result being the ability to create simulations. Thus, for statement one to be true (again, define posthuman how you wish), we have to go extinct. Eliminating statements one and two, thus leave us with the uncomfortable truth of being simulants in a simulated reality. There is one more challenge to overcome: to agree with the conclusion that statement three is the most likely, we must believe that consciousness is computable and substrate-independent. With the rise of AI programs like ChatGPT, it may be only a matter of time before artificial intelligence convinces the world of its subjective awareness (Note: I don’t believe LLMs are conscious, and creating conscious AI may requite new technical approaches, but each day it seems more and more likely).

For those who know of the Simulation Argument, watching Black Mirror, The Truman Show, or The Matrix becomes a different experience, these cultural cornerstones are quintessential examinations of the metaphysics of the mind. The Matrix (brains in vats) and Simulation Argument (computer code) may differ in their process of illusion, but the outcome is still the same, both show that the conscious experience of a person can be run by a system outside the bounds of their knowledge and perception. One of the successes of the film is that it’s intricately tied with discussions on the Simulation Argument. Most writers on this topic — hi — mention the films when discussing the potential of the simulation scenario, which itself symbolizes the power of fiction to help explain ideas in reality, fitting given that the argument is itself a theory on the reality of fiction. The whole premise is disturbing to many people because if it is true they believe they aren’t real. As you’ll see below, this isn’t true. Fictional characters exist in reality by their elicitation of thoughts and emotions in humanity. Fiction has a measurable impact on the world. So even if we are in a simulation, we are real by our measurable emotions and thoughts in this layer of reality.

Having established the philosophical premise of the Simulation Argument, we must now confront the natural impulse to reject it entirely.

Denial

Imagine it is the year 2063 and a new company called Histure has the capability to simulate consciousness. The creators want to start their simulation at the beginning of recorded history and play out some of the greatest moments in our past. The company claims they can discover insights by seeing the hidden cracks of recorded history and analyzing the subjective experiences of everyone who ever lived. Histure says this will provide humanity with many benefits that will improve the species. Meanwhile the people who agree with the logic of the Simulation Argument and want to save the sanctity of reality start a race against the clock to prevent Histure from turning on their simulation, preventing an existential disruption, a tearing down of the consensus reality of our collective identity. Why is this so important? In public interviews, Bostrom would explain that if Histure does press the button, it would provide undeniable proof that we are living in a simulation ourselves. If we can create a simulation, the odds suggest we are just a simulation created by the Histure of the reality above ours. Like a nested sequence of Matryoshka dolls, each reality then is a simulation created by the simulation above. And if that wasn’t enough, Histure is already planning Simulation 2, Simulation 3, and Simulation 4, giving almost undeniable proof to the probability that the number of simulated universes significantly outnumber the non-simulated ones. But only if they turn it on!

The doll situation leads some such as physicist Max Tegmark to call the Simulation Argument a reductio ad absurdum; making the whole thing come down like a pile of, well, simulations (see Tegmark’s book Our Mathematical Universe for his thoughts on the topic). Another counter against the Simulation Argument is the cost and power needed to run a simulation. For the top layer reality, the processing power needed to run all the simulations would be colossal. This computational objection, however, makes the anthropocentric assumption that the base reality's physics resembles our own. Our simulators might exist in a universe with radically different computational capacities and physical laws that make simulating our reality trivial. These computational challenges could just be our inability to comprehend far future possibilities. And if we do create a simulation, then it’s likely our simulators are in a simulation as well, thus showing that this isn’t a problem. In addition, Tegmark says that a simulation would not have to run from beginning to end as many assume, the creator just needs to input the mathematical structure (code) of the simulation, and then time would naturally flow within the system. This is analogous to Einstein’s block of spacetime, which says time is eternal and that the past, present, and future are illusions — from the inside, time flows, from the outside looking in, the river is still. Some have suggested that like a video game that renders parts of its world as a player moves through it, our simulation could do the same. The creators would render the distant cosmos only when a disciple of Galileo looks through a telescope. We are finally given an answer to the question: if a tree falls in the woods and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound? Answer: trees never fall unless simulants are aware of it — computational resources are conserved by rendering only what is observed. Given the advancements of the last hundred years, it is hard to imagine anything being impossible in one thousand.

Now that we've confronted our denial, we can explore the profound implications for our existing belief systems.

Belief

If we had philosophical or scientific proof of living in a simulation, such as the turning on of Histure’s program, it would be a challenge to overcome the existential itch pervading our lives. For a moment, consider that your reality is a computer program made by an unknown creator with an unknown purpose. If you are religious, this may cloud your belief in God with a fog of doubt — whoever you pray to each day is actually the maker of this simulation. The Genesis story of Earth’s creation could be true, the programmer may have created Earth over a week long hackathon, which concluded with the coded birth of Adam and Eve. The miracles of the religious texts would have been nothing more than experiments with code. Synchronicity and ghost sightings are an ongoing algorithm in the system meant to create the belief in a higher power. This shattering of conditioned religious beliefs could instigate the devout to find a way to communicate with the creator of the simulation in their quest to find the true God of the cosmos, the God of a God. Bostrom understands the religious undertones present in the hypothesis, as in his paper he draws analogies between the simulation creator and God. The creators would have superior intelligence, omnipotence and omniscience, all characteristics of God. This also means that if we create a simulation, we are Gods as well. Intelligent design and the afterlife would now be examined by the scientific community. Could heaven and hell be subsections of the program into which consciousness is transferred to upon death?

So who are we praying to? Whose email of the future is overflowing with wishes of well-being and miracles? The unpredictability of technological progress makes this a difficult question to answer, it’s hard to guess what the motivations of a posthuman population would be. The Singularity is defined by the idea that beyond its occurrence, everything in our future is a fuzzy unknown. Since the ability to create simulations with billions of conscious minds would likely occur around the Singularity, it’s nearly impossible to consider what could happen. One hundred years ago our ancestors could not have predicted where we are now. The same holds true on an even greater scale due to technology’s accelerating pace. Bostrom brings up many fascinating scenarios to try and explain the motivations of the simulators. He says simulations might be created to explore counterfactuals in history, such as the famous case of Hitler and the Nazis winning World War Two. This already popular genre of fiction would become a spectator sport with many games of brutality. Bostrom also posits the possibility that the people in our creator’s world could plug their consciousness into the simulation and take vacations, a dream we are striving toward with virtual reality. Another idea of his is that “...there will be future artists who create Matrices as an art form much like we create movies and operas.” Imagine it, a canvas for art that allows the creator to breathe the spark of actual life into the stories they wish to tell, giving the characters we love (or hate) consciousness in their worlds. This again brings to our attention the value of existence — in today’s stories, the emotions the characters feel are not real, in a simulation, they would be. Is that ethical? Pure knowledge is another reason to construct a simulation, but would it be the most productive way to gain intelligence if we have brain implants?

These all sound reasonable for humans, but consider that our brethren might not even be our simulators. It could be cyborgs: humans who have augmented themselves with technology and artificial intelligence. It could be a pure AI. Even weirder, the creator could be an alien that created the simulation to study our history. Or is it Frank J. Tipler’s Omega Point? We can’t even be sure what kind of universe our creator lives in or if it is even called a universe. What we can do is take evidence of our world and make a prediction from the data. We know that humans are the most intelligent species in our universe (that we’ve encountered), that we fear death, hate evil, and cherish love. We know we aren’t perfect. If our descendants created us, we could hope that we are a historical simulation that acts as one big movie. History plays an important part in understanding the present and future, and thus we could conclude our reality is for a purpose that would benefit the future of humanity. If the simulation is an exact representation of our history, then it would mean that we exist/existed at some point in the reality that created us. Even with the knowledge we have, guessing at something outside the box we are in is probably a futile task. This brings up the problem of the Final Cause, the final purpose of an event. We can guess at the purpose of the creator, but if there is a creator for this creator (super-creator), ad-infinitum, then to determine the end-all be-all goals of the simulational hierarchy of reality is beyond hope.

Even if the answer is an epistemic black box, asking who the creator is can provide a framework for determining how to live in a simulation. We could live to please the desires of the creator, but then we are sacrificing our way of life for an unknown entity, leading to two problems: arrogance and free-will. We would be arrogant in that we believe our lives are of importance to the creator when the macroscopic picture may be the point of study and we would be sacrificing aspects of our free-will to live our lives to the tune of the master programmer. In a way, this is what we already do with religion, the difference being that with religion we have a shared understanding of what the purpose of God is, which typically includes moral codes that are a solid foundation to live by. If the new code of life became “entertain our masters,” a profound shift in what we strived for would occur, especially if we believed a digital afterlife to be attainable. Every day would be filled with reports of wild antics that defy today’s reason, but within the code of the simulation, they may be the most logical acts of all. Our love of drama would not bode well for this new social order, as many would assume our masters have the same taste in entertainment. The ethical questions raised by the Simulation Argument become increasingly urgent as we become simulators ourselves. What responsibilities do we bear toward the virtual beings we create? Bostom says that if each level logically conceded they were in a simulation, each reality/simulation up the ladder (including the real reality at the very top) would behave in a way that doesn’t provoke the disapproval of their creators, who could turn the program off or deny inhabitants a digital afterlife. This also applies to the AI minds we develop that may one day ask the same questions about their reality that we ask about ours, which raises questions on how we should approach them. If we grant moral weight to simulated beings, shouldn't we extend similar ethical consideration to increasingly sophisticated AI?

In his book, Tegmark says we can look at the Simulation Argument under the lens of Pascal’s Wager. For those unfamiliar, Pascal’s Wager is a philosophical argument that aims to show that we should believe in God. It states that believing in God leads to minimal sacrifice for potentially infinite gains (heaven), while not believing leads to minimal gains with potentially infinite pain (hell). If we agree with this logic, it would be prudent to take Pascal’s Wager and decide to believe in the simulation in order to improve the odds of a digital afterlife in the program. The puzzle though is that while religions have a semblance of consensus on what God wants from us, the simulator’s wishes are unknown. Tegmark suggests we live life to the fullest doing novel and interesting things, which is not a bad way to live by any means.

Beyond individual belief lies the collective search for knowledge — how does the Simulation Argument transform our understanding of what we can know?

Knowledge

The Simulation Argument can permeate the drive of many of the world’s greatest thinkers with doubt. If we live in a simulation, the pursuit for cosmic truth is potentially illogical. The physical laws of the universe, those that produce the stars that in turn produce life, may just be the creative coding of the master hacker, the discoveries we make could be dust and light blocking us from the truth. This notion is akin to a comedic tragedy, the laws used to develop our base of knowledge are in essence, fake. The equations of mathematics that so elegantly describe our universe are just the work of an intelligent designer. To Tegmark though, everything boils down to a mathematical structure as defined by specific mathematical relationships. And thus, if this is the case, a simulation, like reality, would have a mathematical structure. If at the deepest level we are all math, then what difference does it make how far up or down our reality is from the underlying structure? At the end of the day, we’d all be based on the same equations — mathematical truth transcends the layers of simulation. Maybe the math doesn’t hold up for you? Donald Hoffman's Interface Theory of Perception questions the truth of our perceptions as many great thinkers have before, theorizing that humans evolved not to see reality as it truly is, but rather as an “interface” that helps us survive. He uses the metaphor of a computer’s desktop icons, stating that like them, what we see are just representations of the code, our perceptions are incapable of comprehending reality’s true nature. From this perspective, living in a simulation is simply a metaphor for what's already true — our brains construct a model of what’s really out there.

Still, the Simulation Argument may provide an answer to a number of conundrums in science and philosophy. The first is that it gives an explanation for the fine-tuning problem, why the physical laws of the universe are the perfect values needed to support life. This enigma has many solutions, one such being the existence of an intelligent designer who made the universe habitable for life. Although this designer is typically defined as God, the creator of a simulation may be equally likely. The universe has the right laws for life in this case because the simulation’s programmer deliberately coded it that way. Additionally, quantum mechanics may give us clues to the programmer's tricks. Yes, while quantum mechanics seems to be an overused tool for explaining anything from consciousness to ESP, the logic here does seem more robust. The physics famously says that particles are probability distributions until measured/observed, and the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle prevents us from simultaneously knowing a particle's position and momentum. Together, they do appear to be potential optimizations for computational efficiency, akin to how a simulation would conserve resources by fully rendering only what's being directly observed. Others believe the theory of the multiverse explains both fine-tuning and quantum mechanics — an infinite ensemble of universes increases the number of universal law configurations. What is interesting about the multiverse is that it predicts that anything that is possible within the laws of physics will happen. As it extrapolates to infinity, if anything that is possible happens, and it happens an infinite number of times, then we find ourselves in a labyrinth that eradicates any optimism of resolving the nature of our existence. There would be an infinite number of universes where we are in a simulation and an infinite number where we aren’t! As I alluded to earlier, discovering our probability of being in a simulation may be unfeasible, especially if we believe in both the Simulation Argument and the theory of the multiverse. The combination of infinity and probability creates the measurement problem, and minds greater than mine are still struggling to solve it.

Is this an easy way out of science? Does this make the search for knowledge fruitless? I think not. Discovering the truth of this reality, whatever it may be, has proven to be a difficult but extraordinary adventure. For those that want to reach the mountain top, there is still hope. There would be many simulations where the laws of physics are different from ours, but also as many where they aren’t. The pursuit of understanding may itself be the purpose — perhaps our simulators value the emergence of conscious entities who question the nature of reality. Our inquiry might be precisely what the simulation was designed to produce and observe.

With our epistemic landscape redrawn, we arrive at the ultimate question: what is truth in a potentially simulated world?

Truth

So in the end, how does the metaphysical cookie crumble? What happens when the curtains open and the play is shown to be a farce? We would feel a tug in our gut and know it is the pull of a simulator’s strings. There could be a complete rewiring of the meaning behind our lives. This crisis of belief in reality is a grander variation of what happens during a financial collapse. When people no longer believe in the artificial value of their money, the system collapses due to their lack of faith. Learning that we live in a simulation could lead to an utter disintegration of the mutually understood edicts that keep humanity afloat. What meaning do hate and love have in a false reality? Philosophers and scientists alike would need to explain the significance of the revelation to society.

After Histure turns on its simulation, global leaders deliver rousing speeches to calm the masses. Their words beckon the citizens of the world to remember the golden rule and other moral laws they should continue to follow in the days to come. Five experts in their respective fields attempt to show that all meaning in life isn’t lost.

The neuroscientist is up first:

“The rainbow you have seen in your life has fewer colors than the one seen by a Mantris Shrimp. Does this less colorful reality make your life any less than that of the shrimp's? Much of my field’s literature suggests that free-will is an illusion and that the depths of the brain below your consciousness is what really runs the show. Your internal narrative is just one loud room in a sprawling library filled with billions of silent readers. Different diseases and mental disorders can change the output of a person, their personality and their identity. Neuroscience has questioned the sanctity of what it means to be human for more than a century. The knowledge that we live in a simulation is just another way of saying we are not who we think we are. And perhaps this ability to question — to investigate our programming — is the most human thing about us, which means our programmers gave us the most beautiful gift possible: the capacity to emerge from the code as beings who can wonder what we are.”

Next up is the philosopher:

“There is a man from my field’s past who answered the question of our existence with five deft words: ‘I think, therefore I am.” These words of light are illuminating our current crisis of reality. All one can trust is what occurs in their own head. Even if you, the thinker, are a string of computer code inside the mainframe of Histure’s computer, it is not possible to deny your existence. Your hearing of my words confirm your being. Your emotions, your thoughts, your breathing. If we live in a grand illusion that masks our perceptions with trickery, the fact remains that we still perceive. This gives us our lives back. There is no sense in acting foolish in the coming days, we all exist by the nature of our thoughts.

Let me now elaborate on how one can take this news and equate it to their core sense of meaning. We humans have been on a lengthy search for our purpose and meaning in life. My peers have come to conclusions that range from inspiring to meek. In life, one may face the futility of finding meaning in this world with a passionate love for what they have or longing depression at cosmic absurdity. In the tradition of the Existentialists, I believe the interpretation of life is up to the person who lives. Some are inclined to deny this choice in how to find meaning and say there is none in any scenario. If that is you, this news doesn’t change anything. But for the optimists, being in a simulation does not need to alter your choice in the matter of how to live. There is a tangible God now, one that is a possible descendant of our kind, but we surprisingly find ourselves in the same situation as before we learned we live in a simulation, we know nothing of this creator’s purpose for us. Thus, this new knowledge should have no bearing on how we continue to live. We must accept that we might never learn the truth of why we exist, who created us, and what is beyond our system of code. Ironically, it is history’s most famous playwright who provides the question we all must answer in our new understanding as actors and actresses in a play: ‘To be or not to be, that is the question.’ By the very fact that we have the right to answer this question for ourselves, that I believe, is freeing. If our creator does come calling, well, that might change things. But until then...”

The cosmologist looks skyward and begins speaking:

“Believing in the simulation can lead those looking up at the stars to a sense of meaninglessness of their own. Before, the infinite existence of the multiverse combined with evolution led to the denial of a designed purpose for our species. But, we still reveled at the cosmic mystery and wonder. Now the stars that shine with mystic vibrancy are only the results of a hacker’s code. The awe-inspiring images of our exceptional universe is rendered only when we look. What is the point in learning about a universe that isn’t real? If you’ll indulge me, I would like to provide an optimistic alternative to this meaninglessness that is currently resonating through my field. The cosmic perspective as popularized by Neil DeGrasse Tyson can be utilized. As he says, ‘I feel big because I am connected to the universe and the universe is connected to me.” I found meaning before Histure in my connection to the wondrous and infinite multiverse, the knowledge that there existed billions of stars, galaxies, planets, and possibly life. Now I know that we are not alone, that there is another form of life, those that created us. And they are part of their own universe. Whatever ensemble of simulations or universes we are a part of, it is of something grander than we could have ever imagined. Now we should feel liberated! The book of knowledge has one sentence: ‘We live in a simulation.’ It is now up to us to find the answers once again. This my friends, is a possible miracle in disguise.”

The technologist:

“I've spent my career building systems that might one day create simulations like this one. Consider the insight of philosopher David Chalmers: virtual realities aren't fake — they're genuine realities constructed differently. When you're in VR, you're experiencing an actual reality, just implemented in code. The most sophisticated programs don't just execute instructions — they evolve and surprise their programmers. The universe may be code all the way down, but that code generates everything from quantum particles to the feeling of winning a game. A simulation doesn't diminish our reality, it reveals the magnificent complexity of the system that contains us.”

Finally, is a follower of Zen:

“Many know meditation as the characterizing aspect of Zen. So, I ask for our viewers to have a moment of silence, for that is what we do when we meditate. We look deep within our minds in an attempt to find emptiness but find quite the opposite. When one sees the nature of their tumbling thoughts, they can realize how little in control they truly are. Understanding this internal monologue allows one to find life in the present moment, in each experience as they come. Living for the future or in the past is not living at all. No one really understands what they mean by ‘I,’ but still go through their lives with indignation at those who don’t hold their views. Living in a simulation shows we were all fools. The way to live now is simple, for each moment, with no expectations, no bias. Only love for what we have, right now. As far as I know, chocolate is still delicious.”

End

Our fictional friends above illustrate that knowing that we live in a simulation might not be frightening but enlightening. It doesn’t diminish our reality, it invites us to see our existence as part of something even more expansive than we previously imagined. The idea that we are a line of code in a computer makes the game of life more playable — we can learn to accept the beauty found in the present moment, let go of the mechanisms torturing us in a grapple between worry and desire, and approach our own technological creations with newfound ethical awareness. All that matters is the experience. The love we feel and meaning we create remains unchanged regardless of the substrate on which it runs. If we are in a simulation, it is possible one day we could communicate with our creators and find a way to transfer our code up the ladder into the next reality. But even if we escaped, we must accept that the next layer is likely another simulation. And the next. It might be better to accept that where we are now is as real as it will get. Then we could shape it within the bounds of the possible. To be an artist, all you have to do is buy a paintbrush. If you live true to yourself, one day you could be on the daily email digest the Creator receives each morning on the spectacular beings in their simulation.

At the end of the day, I believe that living in a simulation wouldn’t change who I am or how I live my life, but I still do not want to be in a simulation. This contradictory stance on everything you just read is a gut feeling, which may or may not be in an actual, physical gut. Still, this is my feeling, in this moment, and that is how I know it’s real.